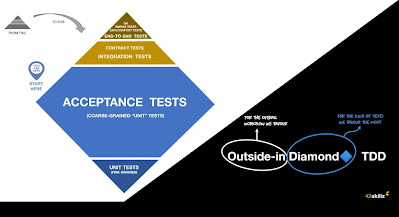

After talking about the WHY and the reasons that have motivated the emergence of this style of TDD over the years (basically, being compatible with people's psychology and helping them with their recurring misunderstandings about TDD), this second article will be about the HOW. To do this, we will see some examples and list the main characteristics of tests written with this style.

Note: For those who would like to know more about it, you can refer to the talk I recently gave to DDD Africa, available here: https://youtu.be/djdMp9i04Sc or to the first article of this series (exploring the WHY)

First, it's a workflow

Before we see the various kind of tests Outside-In Diamond 🔷 TDD cares about, I would like to focus on the writing dynamics of these.

As its name suggests, Outside-In Diamond 🔷 is a style where we draw the shape of our System-Service-API-Application from the beginning based on our use cases and business needs (which each turn into acceptance tests). The ability to drive everything from the outside (i.e. from the consumption of our System) allows us not to get lost along the way and to avoid coding useless things that would not be directly necessary for one of our use cases. This is what makes this TDD-style devilishly efficient. But nothing new here (or related to Outside-In Diamond 🔷). It's just classic old Outside-In bringing its intrinsic benefits.

A frugal style

Indeed, this outside-in dynamic (through exclusive external uses) combined with triangulation allow us to stick to the YAGNI principle (You Ain't Gonna Need It).

One may notice here that triangulation is more often associated with classist TDD (i.e. Inside-Out workflow) than with Outside-In TDD. And that's one of the reasons why it is often complicated for some TDD practitioners to realize that these are orthogonal topics.

As with the traditional double-loop presented by Nat PRYCE and Steve FREEMAN, we start by writing a first acceptance test against a black box (i.e., our System-Service-API-Application) which does not yet exist and whose outlines will be sketched from our interaction with it.

For instance, if I'm coding a web API, my subject under test -the entry point of my black box- will usually be a web controller on which I'm going to call a public method (i.e. our very first Operation for this System-Service...).

Once our very first test is red (RED), I will generally turn it green as quickly as possible, by hard-coding in my web controller the response expected by my test (GREEN). The refactoring phase will undoubtedly be an opportunity to do some design by bringing out a hexagon type (if I'm using an Hexagonal Architecture) or any facade for my domain (REFACTOR).

I will then continue by writing a second acceptance test (notice that we are still in the big loop), which will usually suggest another case for the same operation (RED). To turn green as quickly as possible, I will usually add another hard-coded value in my implementation code, while preserving my first case-test using an if statement (GREEN).

The refactoring-design phase will then serve me to perhaps introduce a right-side port (in the hexagonal architecture sense) in order to start replacing the hard-coded value in my domain by a value found or computed from another hard-coded value returned by my right-side port. Usually, this will slightly impact the initialization code of the test by injecting the right-side port (interface) to our SUT/Subject Under Test. In our case: our web controller (REFACTOR).

One and a half loop... and not a mockist style

At this point, I still haven't written a fine-grained test (the one belonging to the small/inner loop), and I'm about to write my 3rd acceptance test (still in the big loop). This will add a new case to be handled by my current API operation (RED). And this is where triangulation comes in.

In the context of TDD, Triangulation is the fact of generalizing an implementation only from the second or third (hard-coded) case.

Let's see that in action.

Here we can make our 3rd test pass as quickly as possible by adding a second if statement and a third hard-coded value (GREEN). Then we can dedicate our design step by refactoring our implementation in baby steps mode and through what looks like a strangler pattern strategy (as once pointed out to me by my friend and talented eXtreme Programmer: Philippe BOURGAU).

This can be achieved by positioning our new domain material in the implementation code just before the existing if statements. Once our old implementation is eclipsed by the new one, we can remove all these hard coded values from our code (REFACTOR).

The idea is to move with baby steps and without our tests being broken (note: in C#, I'm working with NCrunch, a live test runner that automatically builds and runs all my tests in the background as soon as I change my code. This is really helpful and acts as gamification in order to be always GREEN during the REFACTORING step through baby steps).

Having mostly Acceptance tests does not mean that we aren't taking baby steps! (far from it)

This is the appropriate moment to create intermediate fine-grained (unit) tests in what we call the double or small or inner loop. My personal heuristic over time is to only write those tests if I feel the need for it (ie when facing with a difficulty or when being in a "tunnel effect" for more than 10 minutes).

In the end, the Outside-in Diamond 🔷 style doesn't put too much pressure on writing lots of little fine-grained (unit) tests. It's à la carte (depending on the maturity of the people I'm mobbing or pairing with).

Moreover, these intermediate tests are very often removed once the implementation is complete. A bit like removing wedges and wooden battens that helped us assemble a concrete wall when it is dry.

I will probably come back to the Outside-in Diamond 🔷 workflow later (and how it fits with design decisions) in an upcoming live coding session. That should be easier to illustrate all this.

Now let's see what the Outside-In Diamond 🔷 TDD acceptance tests look like.

Focus on our Acceptance tests

Yes, let's zoom-in on our favorite tests (the Acceptance ones). These are:

- Short: no more than 7-15 lines of code per test. To achieve this we use builders to initialize the test context, fuzzers to quickly and randomly generate values, and helper methods for intention-driven assertions (expressed in 1 line). In addition to relieving our mental load when reading our tests, the advantage of having short tests lies in having as little "implementation detail" as possible and as "intention" oriented as possible. Intentions are generally less fragile than implementations.

- Domain-Driven: Indeed, our tests should express Domain concerns with words belonging to our considered Context (see “ubiquitous language” and "Bounded Contexts" from DDD). We will particularly use builders to declare business intentions, and not getting lost with implementation details. Good test builders publicly expose domain intentions and behaviors, and fully encapsulate implementation details and stub configuration privately.

- Blazing Fast: between sub-millisecond and 400 milliseconds max per test. To achieve this, we will use stubs to be able to avoid any I/O (always more expensive in terms of latency budget). Stubs will only be used for systems external to our System-Service-API-Application. Warning: Outside-In Diamond TDD is an outside-in style, but it is not a "mockist" style.

- Isolated and autonomous: no use of member variables or mutable private fields belonging to the test suite | fixture. No initialization via [Setup] methods for the test suite | fixture either. Even if we use builders and fuzzers, any creation (with its intentions) must be declared from the test and stored in local variables (inaccessible by other tests). This helps to avoid the cognitive overload that occurs when people have to go elsewhere to check what is already prepared or initialized before each test. And please, don't get me started with the painful TestFixture|Suite inheritance and setup made in a TestSuite base class ;-)

- Deterministic: even if we intensively use Fuzzers which propose random values, a means must be provided (in general by the fuzzing library) to be able to replay the same Test under exactly the same conditions (in general by reusing the same seed). This is essential in order to be able to reproduce and understand any failure that occurred once in a test execution (on the software factory or on a dev workstation).

- Behavior-driven: we try to hide everything that is technical. These tests are always doing the same thing: we ask our black box (to do) something and we check that its answers suit our expectations. The checks (or assertions made) are generally encapsulated in test helper methods that allow us to be concise and business-oriented (regardless of the assertion library you use and the number of checks).

- Similar: We highly rely on the power of sameness (for instance to reuse the same variable names for the same domain concepts across tests) in our test code in order to smooth our future tests refactoring (e.g.: to ease possible search and replace). We consider our test code as production code. We improve it and refactor it regularly too.

- Antifragile: by default, thanks to all the features mentioned, one can easily change and refactor our implementation code without breaking contracts exercised by our tests. To put it another way, our tests age well and don't break when we change the internal structure of our code. They should only break if we introduce a bug or a regression.

- Broad spectrum: even if they hide it well (thanks to builders and helpers), our Acceptance tests cover a broad spectrum of our code base and include the real adapters in case of hexagonal architecture (instead of subbing them). This is the opposite of what people usually recommend, but this is the most effective testing strategy that I have ended up over the past 8 years of putting hexagonal architectures in production (in different contexts and for different customers). Since this is more than an Argument from authority ;-) I will dedicate the next article to illustrate and explain all these trade-offs.